Project 562 Gallery: Dreams becoming real

Darkfeather Ancheta, left, is pictured with her nephew, Eckos Chartraw-Ancheta, and sister, Bibiana Ancheta, on the shore of Tulalip Bay. The family adorns in traditional regalia for our annual Canoe Journey. This celebration has been indispensable to Darkfeather as a person of the Coast Salish Sea.

“It didn’t change me. It shaped me. It’s just who we are, and where we come from. It revitalizes our cultural ways. We take care of the canoe and it takes care of us. When we’re on the water, we all have to pull together. The teachings that the elders gave to us, such as respecting ourselves, respecting each other, respecting other people’s songs, their dances, and their teachings—they teach us how to walk in the world. And the music and songs are so powerful. It’s all so beautiful. It touches you down into your soul. It helps you get through hard times, both inthe water and in life.” Bibiana reflected on “the journey” as part of a crucial Indigenous perspective and cultural and personal practice. “In man’s law, sovereignty is an illusion of independence under dependence. Under nature’s law, it’s a Creator-gifted right, handed down through our ancestors. Passing down our knowledge, cultures, traditions, and language is vital to our survival, helps root us in our ways so we always know who we are. Without this, we become just another human being with no identity; you risk being spiritually lost. Identity comes from our culture, our culture comes from our language, and our language comes from our environment. So, to protect our environment is to protect ourselves.”

https://www.project562.com/11397500-gallery

This morning I did yoga with Darkfeather, and she reminded that all of this was a dream. She remembers when I was dreaming about making @project_562 real. She remembers when I called her and told her about this image that I saw first in my dreams. I truly believe (especially today on Earth day) that the spirit and the earth will send us messages in our dreams, and if we can muster the courage, we can turn dreams reality.

I always think about that as I see canoes on the water. Our ancestors, despite religious and cultural persecution, dreamt of maintaining these life ways. So now, every year, 100+ U.S. tribes, First Nations and Maori canoe families make “the journey” by pulling their canoes to a host tribe. Canoe families pull for weeks, and upon landing, there will be several days and nights of cultural celebration.

Sisters, Darkfeather(left) and Bibiana (right) expressed this so clearly in their interview with me stating, “When we’re on the water, we all have to pull together. Everything is smoother when we all work together. The teachings that the elders gave to us... ...they teach us how to walk in the world”. -Darkfeather Ancheta.

Across the country, Tribal Nations are calling for the protection of places sacred to them. Even though they are the original stewards of America’s lands and waters, they are too often left out of decisions about our public lands. Honoring their ancestral, cultural and economic ties to the land is essential for celebrating how Native peoples contribute to all of us who love the outdoors.

Let’s support the calls of Tribal Nations for the permanent protection of sacred places on this Indigenous Peoples Day (and every day).

Join us in urging President Biden to safeguard the future of these lands.

Let's mobilize to protect America's public lands.

Every 30 seconds, America loses a football field’s worth of natural spaces to development and other pressures. What's more, today we face the dual challenges of more extreme weather events and more than 100 million people in America who lack access to green spaces. Now is the time to double down on efforts to protect America’s most precious places.

Across the country, Tribal Nations and other communities who have too often been left out of decisions about our public lands are calling for the protection of places sacred to them. REI, in concert with hundreds of organizations and outdoor brands, is joining these leaders in calling for national monument designations that will ensure the future of spectacular cultural sites and critical habitats—for ourselves and for the future outdoor enthusiasts who will follow in our footsteps.

Protecting these places as national monuments is also a key solution for ensuring that more of us can access world-class recreation opportunities and sustain rural outdoor recreation economies nationwide.

Our nation’s natural beauty can’t wait. Urge President Biden to protect America's most precious places today.

About Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument—Molok Luyuk Expansion

About the Chuckwalla National Monument and Expansion of Joshua Tree National Park

https://www.rei.com/action/network/campaign/monuments

For thousands of years, more than 60 Native American tribes lived in Oregon's diverse environmental regions. At least 18 languages were spoken across hundreds of villages. This civilizational fabric became unraveled in just a few short decades upon contact with white settlers in the 19th century. In this "Oregon Experience" documentary, Native Oregonians reflect on what has been lost since and what's next for their tribes.

Every Person Living In The Northwest Should Know This History

In August, fifteen thousand people welcomed more than one hundred canoes to Puyallup. It was glorious. I felt proud to be a Coast Salish woman. I felt proud to be born from these people.

The Coast Salish Sea has always been known as the life blood of our people— Mish’s or ‘the people’ in Lashootseed belong to her— we know ourselves as “the people of the tide,” “the people of the clear salt water,” and other water- and land-based identities. This water provided life for us as we traveled our ancestral highways to maintain our vibrant economies, to ensure that our nation-to-nation relationships remained strong, and to keep us alive. The dugout canoe served as our vessel to travel long distances, ensuring sufficient quantities of food, establishing and renewing tribal alliances, and preserving social and ceremonial contacts, which in turn permitted our culture not only to survive, but to flourish. The canoe served as the locomotive engine to industrialization and provided the harmonious, potlatching way of life that endured for thousands of years.

Our way of life remained until the colonizer arrived.

At the turn of the 20th century, the federal government wanted our people to vacate our longhouses, to relocate to our 40 acres, and to distance ourselves from our traditional life-ways. We were meant to become farmers and assimilate to American culture. Indian agents were assigned to verify our level of assimilation so that we could be citizens. Many of our people refused. We liked our way of life. We liked living in longhouses, with entire families, feasting and laughing. The idea of a single-family house sounded absurd. Besides, we were fishermen. Become farmers? Pah, we refused to leave our longhouses. The cavalry responded by setting our longhouses aflame. Massive dwellings like Old Man House blazed in terror. Our ancestors fled to the islands in our canoes, pulling to safety from the cavalry (horses can’t swim as fast as canoes pull). The feds responded by outlawing our canoes, making it illegal for us to even be in them. They destroyed our canoes by burning them or sawing them in half. Even today you can visit our canoe bone yards in the woods. As they had destroyed our canoes, so too the feds declared war on our bodies, saying that any gathering of five or more Indians would be considered a war party.

That is when “canoe life” went to sleep.

Our lives were forever changed. With our homes destroyed and our vessels and food systems disrupted, we were left no choice but to move. We were made homeless in our own homes. In this Godless way, we Mish’s were forced to move onto reservations and there we remained until finally, through the Indian religious freedom act in 1979 we were legally allowed to return our spiritual vessels to the water.

Fast forward ten years to the city of Seattle celebrating its centennial. The city officials called the indigenous people and asked for Native representation. Specifically they called upon Emmett Oliver from the Quinalt Nation. Imagine that, a city celebrating its colonial settlement and asking the very people they displaced to help them celebrate. The un-thanksgiving, if you will. But our elders went. They desired to resurrect those bones and reconnect with our stolen waterways, even if it was in the name of colonial positioning. They knew deep down that this was their platform for resurgence. In 1989, 17 canoes participated in the first Paddle To Seattle. I was just five years old. A few years later, our people paddled to Bella Bella. Every year since then, the “canoe families” have been paddling to a different host destination.

Throughout my lifetime, I’ve paddled on various canoes. I’ve paddled with Alaskans, Tulalips, Nisqually’s, Quinalts, Urban Indian Inter-Tribal Canoes, and even some canoes in Haudenosaunee and Anishinabe territory. When I was a kid my Mom would always encourage me to go paddle— I’d always decline. I didn’t get it. I didn’t know that it was a privilege. It didn’t really fully sink in for me until two years ago when I was in Nisqually, and Hanford Mcloud told me the story of Chief Leschi. Of how he was hunted down and hung for refusing to sign the medicine creek treaty and wrongfully accused of charges he didn’t commit. What stuck out to me is the way that people came for him. Of how they circled the jail house the he was kept in. And how they kept the drum beat going for him until the day he was hung. On that day, Chief Leschi told the people that there would be a great loss ahead but to remember the water. To remember the mountain. To remember where we had come from. And that a day would come when our spirits would be strong again, and on that day, he’d be there with us.

When hundreds of canoes landed in Nisqually, a chair stood, waiting for Chief Leschi.

The canoe is more than just a vessel to carry our bodies; it carries the hope and resiliency of our people. We are living in a time of cultural resurrection, The Coast Salish sea beckons our bodies to commune with the ocean in our traditional way— to provide the lifestyle needed to feed our people. The elders say that our spirit gets hungry. Our spirit isn’t just hungry for food. It needs to be nourished by the sound of water pulling and drum beats tapping; it yearns for traditional Salish seafood that burns over open fires and emerges from beneath the smoldering ground; our spirit grows hungry for the feelings that can only be sensed in those spaces. Traveling these ancestral waterways reinstates our wholeness as a people. These spiritual voyages embody the resilience of indigenous sovereignty. This is a revolution.

+++

Living and Connecting Outdoors

Day-to-day, I’m a cultural educator for my community here at Muckleshoot. The tribe owns about 96,000 acres at the base of Mount Rainier, which is Tahoma or Ta Ko Ba to us, and I get to take the community outside and connect them to the land. I talk about plant medicines, and how to bring tribal food sovereignty into our homes by utilizing our native plants.

I also have what’s called an “earth gym.” I work youth out using the land: squatting down on a log, throwing rocks over a tree stump or bending over and picking up heavy objects—we use what’s outside. Bringing these kinds of things back into our homes is important for cultural sustainability, as is maintaining our practices that have been lost through generational trauma, assimilation, residential schools—the list goes on. I’m a strong believer in protecting Mother Earth for the seven generations ahead, and I believe the best way for us to do that is through connecting people to the land. Because how can you protect something that you’re not connected to? The only way you can get connected to that is by getting outside.

I grew up in Georgia in the ‘80s, and my parents sent my siblings and me outside often to play. If we were outside, it meant that we weren’t in trouble, we weren’t doing chores—we were with our friends. It was never organized in the sense of my family hiking or any of those kinds of things. But, we were always outside, whether it was wandering through the trailer park or waiting for the pool to open in the summer or walking through the neighborhoods.

Despite growing up outside, I never considered climbing a mountain before this. Mountaineering isn’t something my people have been doing, in part because national parks were actually created to move Indigenous people out of those spaces. They’ve done a really great job of keeping us out. For me, I didn’t see myself out there. There was nobody who looked like me.

Meeting the Mountain

Initially, the mountain didn’t “call me.” I was a competitive bodybuilder, but when I found out I was pregnant with my son, I didn’t feel like I could just pack my bag and go to the gym. But I thought, “Exercise is resistance plus cardio. My son’s going to be my resistance, and we’re going to get outside and hike.” Mind you, I didn’t know anything about hiking. I didn’t know how to find the trail or how to navigate it.

Snoqualmie Falls was the first hike I did with my son, when he was 6 weeks old. We hiked to the bottom and back with him in his little pack, and I thought, “That was a good challenge.” That first hike gave me some confidence. At first, it was always me and him. Then I started looking online for local trails, and then I started inviting people to go out with us. We had 20 people on some hikes. They were looking for connection just like I was looking for my own peace.

Me and my son’s hikes gradually got longer: 2-mile hikes turned into 5-hour hikes, and then our 5-hour hikes turned into overnight camping trips, and then those turned into multiple days on the mountain. The more we got out there to hike, the more I realized, “I never run into any Natives out here.” It got me wondering, why are we not out hiking when the mountain is literally our backyard?

I started asking around, “Do you know of any tribal members who had ever summited? Do you know of any tribal people who had been out there?” And I kept hearing no. I told my significant other, “I think I’m going to attempt to summit next year.” That was in August of 2021, and in October of 2021, I signed up for a June 2022 climb.

I thought, “I was a bodybuilder, I’ve been in the best shape of my life, I can go climb a mountain.” That was dumb shit. It was nothing like bodybuilding! I know cardio and I know endurance, and I knew those things were needed, but I had no clue that the training base that I had was nothing like the base that I needed for this. I basically jumped in the deep end. Three days into my first attempt, I had to turn around and come back. My ego kicked in because I never imagined not completing it. It wasn’t so much about not making it to the top: The true goal of the climb was revisiting my tribe’s traditional plants, taking our medicines, taking our traditional foods and being able to share them with people visiting the mountain. To go back down felt like a walk of shame. There was nothing that YouTube taught me to get me ready for that.

This isn’t about the peaks. It’s about my people. I want to create visibility for us on the mountain.

We’ve Always Been Here: A Healing Journey for a Group of Indigenous Climbers

For seven Native mountaineers, climbing Tahoma (also known as Mount Rainier) is about much more than reaching the top.

On a clear day in Seattle, you can see the ancient face of Tahoma or Ta Ko Ba (təqʷuʔmaʔ), craggy and snow-capped, at once close and far away. On maps and postcards today, she’s called Mount Rainier, renamed in 1872 by a British Royal Navy officer. But before then, Tahoma was a lifeline to millions of Indigenous people.

At 14,410 feet, Tahoma is the highest volcanic peak in what is now known as the contiguous United States. Many parts of the mountain feel wild, but she’s not unaccustomed to human activity: For millennia, Native groups—including the Coast Salish, Cowlitz, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin Island and Yakama peoples—were her close companions, gathering berries and hunting game on her slopes; fishing in her cool, clean water; and collecting cedar to make baskets, regalia, hats and children’s toys.

Today, however, there are few Indigenous visitors to the mountain. After President McKinley designated Mount Rainier as the fifth national park in 1899, Indigenous presence there declined, and white mountaineers and international visitors began dominating recreation in the area. The mountain’s first documented summit was in 1870 by two white Americans; to date, according to Muckleshoot climber Rachel Heaton, there have been no known successful summits by an Indigenous woman. She’s setting out to change that.

Heaton is now the leader of a group of six other climbers, representing a range of Indigenous identities, who have spent time training and preparing themselves to venture far up Tahoma as they can, quite possibly for the first time in recorded history. In early September of 2023, they reached 12,000 feet together, stopped short of summiting by deteriorating route conditions. But their mission is not simply to reach the top: They want to increase Native visibility on the mountain and raise awareness for the ancient relationship between Tahoma and the Indigenous peoples who honor her.

https://www.rei.com/blog/hike/indigenous-mountaineers-climb-mount-rainier

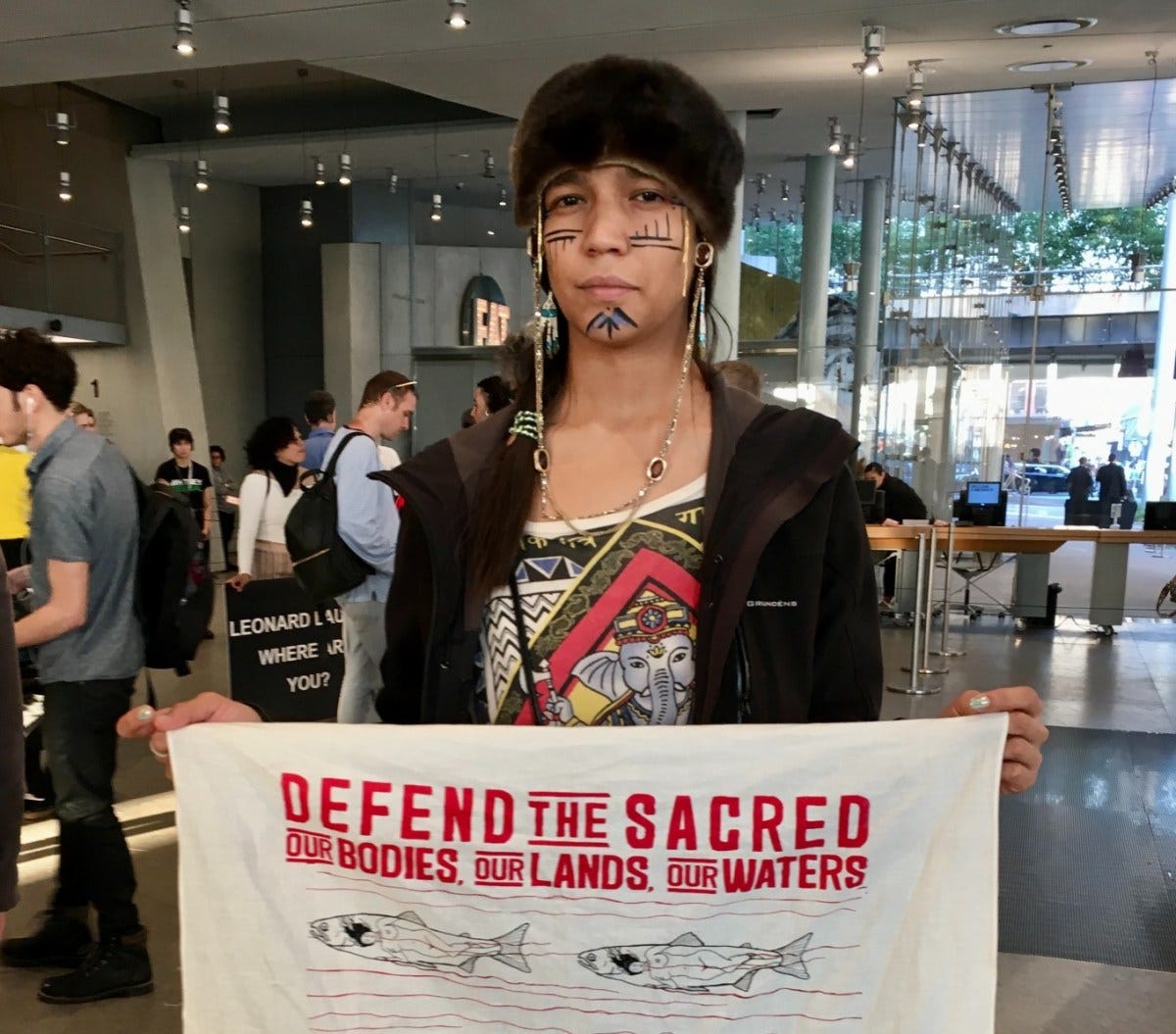

A protester at the Whitney Museum during the "Nine Weeks of Art and Action."

"Our survival is the survival of the forest, and the survival of forests is the survival of the planet. We're on the edge. But until the end, we will be the resistance."

– Mayalú Txucarramãe

Indigenous peoples are on the front lines resisting environmental destruction and advancing true solutions for the Amazon and our planet. Today, as people in the United States honor Indigenous Peoples' Day, we stand with Indigenous partners and say now is the time to secure Indigenous land rights and protect the Amazon, forever!

WILL YOU MAKE A SPECIAL INDIGENOUS PEOPLES' DAY DONATION TODAY?

Indigenous peoples protect 80% (yes, 80%!) of the world's biodiversity. As ecosystem destruction has pushed the Amazon to a tipping point, Indigenous stewardship and climate leadership are critical to averting this ecological disaster. This can only happen if we answer Indigenous peoples' calls now to protect the remaining 80% of the Amazon rainforest by 2025.

Today, we ask you to make a special donation as an act of solidarity with Amazonian peoples. Your gift directly supports:

securing Indigenous land titles and ending extractive industries in the Amazon,

accompanying Indigenous women leaders building pan-Amazon movements in defense of life,

uplifting the safety and well-being of Indigenous Earth Defenders, and so much more.

Thank you for your solidarity with Earth Defenders of the Amazon, on Indigenous Peoples' Day and every day!

The hala of Naue returns home

In case you missed it, back in July keiki from Nā Lauaʻe o Makana summer program helped plant these baby hala (Pandanus) trees at Camp Naue on Kauaʻi's North Shore. Thought to have been lost forever, the famous hala of Naue has now returned home. One day these same keiki will see hala flourishing at Naue once again!

For the full story on the hala of Naue, click here.

We're hiring - Director of Science and Conservation

The Director of Science and Conservation will provide strategic leadership to ensure and enhance the conservation impact of NTBG's science and conservation programs across our five gardens, preserves, and living and herbarium collections. Learn more and apply »

Santa Fe Indigenous Center celebrates on Plaza 2023

Thanks for sharing Jenna! Here’s an excellent documentary about the making of “Little Bird” on PBS (player online) which really gives a great historic perspective of what has happened in our lifetimes (from “60s scoop”) & how a lot of stolen kids from Canada ended up in US: https://www.pbs.org/video/little-bird-wanna-icipus-kupi-coming-home-64jchd/